|

Navigation

Recent Articles

Favorite Blogs

|

|

|

Tuesday, November 4, 2008 - 23:24

|

|

My New President

Congrats, good luck, and godspeed on starting the voyage of a lifetime. We've witnessed history.

(HT: Greg Mankiw for the image)

-----------

I thought Mccain's concession speech was classy and I particularly enjoyed this blurb from Obama's acceptance speech -

And to all those who have wondered if America's beacon still burns as bright – tonight we proved once more that the true strength of our nation comes not from our the might of our arms or the scale of our wealth, but from the enduring power of our ideals: democracy, liberty, opportunity, and unyielding hope.

As we chart a path moving forward, I also thought it would be worthwhile to dig up this "post election pledge" from back in 2004.

Comments [

] Comments [

]

|

Sunday, November 2, 2008 - 10:00

|

|

SM Roundup - IV

Since most of my blogging activity has flowed over to Sepia Mutiny, it's time to post another round up here

Previous SM Roundups - 1, 2, 3.

Comments [

] Comments [

]

|

Sunday, August 17, 2008 - 10:20

|

|

Natural Ain't All It's Cracked Up to Be

|

Friday, July 4, 2008 - 10:00

|

|

How the Rich Spend Their Time

The alternate, more provocative tagline for this blurb could be "The Rich Deserve their $$ because they work harder" -

According to research by Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize-winning behavioral economist, quoted in an article in the Washington Post, "being wealthy is often a powerful predictor that people spend less time doing pleasurable things and more time doing compulsory things and feeling stressed."

People who make less than $20,000 a year, for instance, spent more than a third of their time in passive leisure, like kicking back and watching TV. By contrast, those making more than $100,000 a year (I would call them affluent, not wealthy), spent less than a fifth of their time in passive leisure. "The richest people spent nearly twice as much time as the poorest people in leisure activities that were structured and often stressful -- shopping, child care and exercise."

Comments [

] Comments [

]

|

Thursday, March 13, 2008 - 02:18

|

|

Finnish Kids

One of my standard quips about limits of libertarianism is that it's often silently predicated on a specific underlying culture. In other words, a "live and let live" set of formal policies requires very strong set of informal cultural norms in order to deliver cohesive, productive behavior.

Sans that culture, you have to clamp down pretty hard with formal policy. To take one extreme, Somalia might be a libertarian country in a strict, formal sense due to its almost non-existant formal government. BUT, clearly, the end result isn't quite an ideal and there's clearly something else separating it from pre-NewDeal America... In short, Libertarian Government is a luxury of conservative culture (or, perhaps more accurately, classically liberal culture).

A fascinating small scale case study of this effect was recently described by the WSJ when they examined Finnish schools which are (paradoxical to many) both highly productive and strikingly unregulated -

High-school students here rarely get more than a half-hour of homework a night. They have no school uniforms, no honor societies, no valedictorians, no tardy bells and no classes for the gifted. There is little standardized testing, few parents agonize over college and kids don't start school until age 7.

Yet by one international measure, Finnish teenagers are among the smartest in the world. They earned some of the top scores by 15-year-old students who were tested in 57 countries. American teens finished among the world's C students even as U.S. educators piled on more homework, standards and rules. Finnish youth, like their U.S. counterparts, also waste hours online. They dye their hair, love sarcasm and listen to rap and heavy metal. But by ninth grade they're way ahead in math, science and reading -- on track to keeping Finns among the world's most productive workers.

IQ is certainly one avenue for explaining this but I tend to come down hard on the side of culture. Before a Finnish student even starts school, he/she has already baked in some pretty heady expectations -

...What they find is simple but not easy: well-trained teachers and responsible children. Early on, kids do a lot without adults hovering. And teachers create lessons to fit their students.

...Finnish high-school senior Elina Lamponen saw the differences firsthand. She spent a year at Colon High School in Colon, Mich., where strict rules didn't translate into tougher lessons or dedicated students, Ms. Lamponen says. She would ask students whether they did their homework. They would reply: " 'Nah. So what'd you do last night?'" she recalls. History tests were often multiple choice. The rare essay question, she says, allowed very little space in which to write. In-class projects were largely "glue this to the poster for an hour," she says. Her Finnish high school forced Ms. Lamponen, a spiky-haired 19-year-old, to repeat the year when she returned.

...Once school starts, the Finns are more self-reliant. While some U.S. parents fuss over accompanying their children to and from school, and arrange every play date and outing, young Finns do much more on their own. At the Ymmersta School in a nearby Helsinki suburb, some first-grade students trudge to school through a stand of evergreens in near darkness. At lunch, they pick out their own meals, which all schools give free, and carry the trays to lunch tables. There is no Internet filter in the school library. They can walk in their socks during class, but at home even the very young are expected to lace up their own skates or put on their own skis.

While Finland writ large is unlikely to be the setting for a lesson in libertarian government, the school system presents a pretty nice case of what makes it possible.

[a previous blogpost on a similar topic...]

Comments [

] Comments [

]

|

Tuesday, March 11, 2008 - 09:34

|

|

Income Statistics - II

Brad Schiller takes on the "Median Household Income" vs. "Per Capita GDP" question in a far more professional manner than my earlier blogpost -

...The median household income in 2006 was $48,201, just a trifle ahead of its 1998 level ($48,034). That seems to confirm middle-class stagnation.

[However] Demographic changes in the size and composition of U.S. households have distorted the statistics in important ways.

First, we can easily dismiss the notion that the poor are getting poorer. All the Census Bureau tells us is that the share of the pie consumed by the poor has been shrinking (to 3.4% in 2006 from 4.1% in 1970). But the "pie" has grown enormously. This year's real GDP of $14 trillion is three times that of 1970. So the absolute size of the slice received by the bottom 20% has increased to $476 billion from $181 billion. Allowing for population growth shows that the average income of people at the bottom of the income distribution has risen 36%.

..The "typical" household, however, keeps changing. Since 1970 there has been a dramatic rise in divorced, never-married and single-person households. Back in 1970, the married Ozzie and Harriet family was the norm: 71% of all U.S. households were two-parent families. Now the ratio is only 51%. In the process of this social revolution, the average household size has shrunk to 2.57 persons from 3.14 -- a drop of 18%. The meaning? Even a "stagnant" average household income implies a higher standard of living for the average household member.

And while the household composition has been changing, Schiller also notes that the influx of immigration (legal and illegal) changes the "median" far quicker than the "mean" -

Since 1998, the U.S. population has increased by over 20 million. Nearly half of that growth has come from immigration, legal and illegal. Overwhelmingly, these immigrants enter at the lowest rungs on the income ladder. Statistically, this immigrant surge not only reduces the income of the "average" household, but also changes the occupants of the lowest income classes.

...People keep entering the distribution line from the bottom. Even though individuals are moving up the line, the middle of the line never seems to move. Hence, an unchanged -- or even receding -- median marker could co-exist with individual advancement. The people who were at the middle marker before have moved up the distribution line. This is the kind of income mobility that has long characterized U.S. income dynamics.

And yet, as if on cue, the NYT has an OpEd decrying the situation -

...And if the good times have really ended, they were never that good to begin with. Most American households are still not earning as much annually as they did in 1999, once inflation is taken into account.

...The median household earned $48,201 in 2006, down from $49,244 in 1999, according to the Census Bureau. It now looks as if a full decade may pass before most Americans receive a raise.

Comments [

] Comments [

]

|

Wednesday, February 27, 2008 - 09:30

|

|

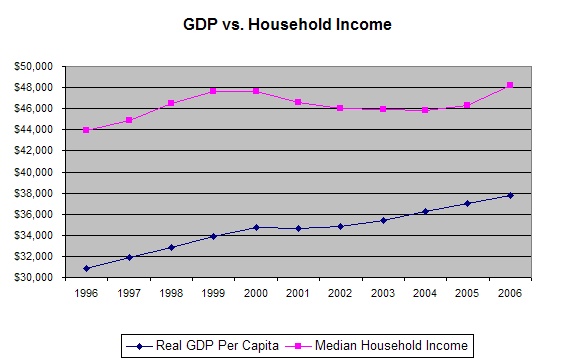

Income Statistics

One of the things that Thomas Sowell points out in this interview is how politicians are able to pick & choose different income stats in order to make different cases. In particular, given election season, he notes that whenever anyone starts talking about "median household income" they're usually trying to make income statistics sound bad.

So, I did some digging to find the stats myself and the divergence between "household income" and "Real GDP Per Capita" is interesting to say the least -

[GDP data comes from here; Median Household Income data is from here]

Why the delta? Well, the key words are "median household".

On the "household" side, demographics are changing dramatically. For example, young single working folks (women in particular!) are far more likely to live in their own households now vs. in the past. That combined with smaller families and more homeowners in general means that a given basket of income is spread over a larger number of homes. Thus, and somewhat perversely, more flexibility in living status brings down this statistic significantly.

Similarly, the point in the distribution that's represented by "median" (rather than the "mean") is also changing dramatically. Broadly speaking, the mean fluctuates less with changes in the distribution curve vs. the median. For example, new immigrants (illegal or legal), fresh college grads, and the like populate the low end of the curve and enter the labor pool at a relative income level that hasn't changed much in the past few decades. Today's grad students live at about the same income level as 20 yrs ago, AND there are a lot more of them, AND their incomes due to grad degrees will be far greater. Additionally, phenomena like "assortive mating" as high income women seek out high income men skews the distribution vs. the old skool when men were more likely to marry housewives.

Wikipedia notes these effects from 1969 to 1996 and there's every reason to believe they continue to be the case in the dataset I highlighted above -

In 1969, more than 40% of all households consisted of a married couple with children. By 1996 only a rough quarter of US households consisted of married couples with children. As a result of these changing household demographics, median household income rose relatively slow despite an ever increasing female labor force and a considerable increase in the percentage of college graduates.

Comments [

] Comments [

]

|

Wednesday, February 20, 2008 - 15:01

|

|

More Sepia Mutiny

And now, even more of my recent Sepia Mutiny posts -

Some previous Sepia Mutiny compilations

Comments [

] Comments [

]

|

Tuesday, December 18, 2007 - 09:41

|

|

Consequences & Intentions

One of the classic dividing lines between econ-minded and lay people is that between consequences and intentions. Econ-folk are generally consequentialists and tend to judge an action by it's real world impacts. The belief system was perhaps most famously articulated by Adam Smith as -

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

In other words, we don't care what the Intentions were of the baker; we should only really about the object he produced. His reasons (be they benevolent or otherwise) are his, his alone and, strictly speaking, should be independent of whether or not we consume his bread. In many respects, the whole machinery of capitalism relies on this sort of evaluation of "product" independent from "intentions" as a solution to Hayek's Knowledge Problem; it would simply be computationally impossible to make / buy / sell complex goods without "market price" as an informational shortcut.

For better, this mechanism is a large part of how capitalism is able to scale across different cultures and, for that matter, across people who may hate each other. In fact, this is why so many argue that capitalism is such an effective weapon against racism. For worse, this mechanism leads to a sort of alienation felt by many that's been the subject of numerous tracts by activists large and small.

A key insight into the latter was highlighted by Steven Pinker in his prodigous literature on Human Nature. While markets writ large are products of the last couple thousand years of human civilization, the human brain's "native" social circuitry was formed by evolution over hundreds of thousands of years to assess dominant transaction types that occurred well before. Consequently, chunks of the brain are 'naturally' hardwired to divine the intentions of the parties involved regardless of the economic impact on the transaction. By contrast, Econ-brains aren't quite so natural and, like math or science, are more the product of explicit schooling.

Thus, the argument goes, we have one reason why so many folks have deep seated, emotional reservations about capitalism -- a sort of vestigal, cognitive bias leads us to question the baker's Intentions / Motives and Selfishness leaves us feeling uneasy. Is he really trying to make us great bread? Or just make a quick buck? And if he's a giant baking corporation, he's even more faceless and profit-driven. I'd argue that a good chunk of the work of corporate marketing / branding is, in fact, an attempt to bridge the divide between "what is produced" and "how we assess the producer's intentions".

An interesting article in the NYT dives into a new fad in philosophy - dubbed Experimental Philosophy - and presents an interesting quirk in our Intentions Circuitry . In addition to "naturally" seeking an intentions basis for market behavior, there's apparently also an assymetry in how rapidly we assess Good vs. Bad intentions -

Suppose the chairman of a company has to decide whether to adopt a new program. It would increase profits and help the environment too. “I don’t care at all about helping the environment,” the chairman says. “I just want to make as much profit as I can. Let’s start the new program.” Would you say that the chairman intended to help the environment?

O.K., same circumstance. Except this time the program would harm the environment. The chairman, who still couldn’t care less about the environment, authorizes the program in order to get those profits. As expected, the bottom line goes up, the environment goes down. Would you say the chairman harmed the environment intentionally?

I don’t know where you ended up, but in one survey, only 23 percent of people said that the chairman in the first situation had intentionally helped the environment. When they had to think about the second situation, though, fully 82 percent thought that the chairman had intentionally harmed the environment. There’s plenty to be said about these interestingly asymmetrical results. But perhaps the most striking thing is this: The study was conducted by a philosopher, as a philosopher, in order to produce a piece of . . . philosophy.

Other commentors like Arnold Kling are skeptical that experimental philosophy will generate useful insights. I'm more optimistic that, as with other studies into cognitive biases, that understanding the basis of our flaws is a big step towards solving them.

Comments [

] Comments [

]

|

Wednesday, October 31, 2007 - 14:04

|

|

Ode to Civil Society

I really liked this passage from Nobel-laureate Ronald Coase describing a difference in the way civil society and government hypothetically act -

If a federal program were established to give financial assistance to Boy Scouts to enable them to help old ladies cross busy intersections, we could be sure that not all the money would go to Boy Scouts, that some of those they helped would be neither old nor ladies, that part of the program would be devoted to preventing old ladies from crossing busy intersections, and that many of them would be killed because they would now cross at places where, unsupervised, they were at least permitted to cross."

It's important to note that "liberal vs. conservative" difference in Coase's ad absurdum example isn't about goals - ostensibly, both Boy Scouts and government do-gooders want little old ladies to be able to cross the street. Instead, it's about processes.

Unfortunately, too much political and social discourse is directed towards steering the government rudder with little credit given to these other organs of collective action. And as a result, too many folks assume that not supporting the government process (be it in healthcare, poverty, minorities, or, little old ladies) is somehow tantamount to selfishly / evilly opposing the goal.

Comments [

] Comments [

]

|